Background

The introduction of both the Electronic Money (“e-money”) Regulations [2011] and Payment Services Regulations [2017] has promoted significant innovation and additional competition in the United Kingdom’s (“UK”) financial services market. UK consumers can now choose from a wide variety of brands when it comes to managing their finances and facilitating payments through digital channels.

By way of example, under the e-money regulatory regime, a new entrant can establish a brand and customer base by issuing a pre-paid payment card, alongside a digital app, sort code and account number, all without having a banking licence. Funds can then be transferred to an account with immediate availability to spend on a payment card, similar to the current account and debit card functionality offered by a bank. Fast-growing banks such as Monzo and Kroo took this approach before receiving their banking licences.[1]

Another popular use of these regulations is to facilitate foreign exchange and cross-border payments, such as Wise and Revolut. As these businesses grow, they often evolve to provide services that are similar to banks, e.g., by adding payment cards and investments. In some cases, they then seek a banking licence to be able to accept deposits, provide consumer loans and mortgages. Revolut is an obvious example, although its application is yet to be granted.[2] Further uses of e-money include open banking applications, digital wallet providers, travel money and gift card providers.

However, if a retail customer has funds held with an alternative (non-bank) service provider (“alternative providers”), such as an electronic money institution (“EMI”) or payment institution (“PI”), the Financial Services Compensation Scheme (“FSCS”) does not apply.[3] When funds are transferred to one of these institutions, this is done on the premise of making a payment. This means, the funds are not considered to be a qualifying, protected deposit. These alternative providers cannot pay interest or use the funds in the course of their own business activities and must only hold the funds for the purpose of processing payment transactions.

If one of these alternative providers fails, the customer is then reliant on whether the firm has effective ‘safeguarding’, investments, or insurance to enable their money to be returned. That process is unlikely to be quick, and then introduces the risk that the customer may not get their money back in full.

Size and growth of the market

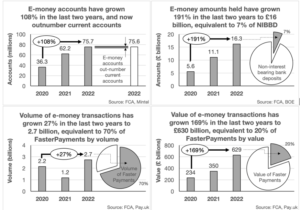

As of 30 March 2023, according to the Financial Conduct Authority (“FCA”) there are 254 EMIs and a further 944 PIs regulated in the UK.[4] The number of e-money accounts now out-numbers current accounts at 76 million, with £16 billion held at the end of 2022. The value and volume of transactions has grown significantly over the last two years, with over £630 billion transferred in 2.1 billion transactions during 2022.[5]

As the above charts illustrate, the EMI world is no longer a peripheral element of the UK financial sector, with volumes and transactions growing exponentially. In addition to Credit Suisse, the United States of America’s (“US”) banking sector has experienced significant turbulence this year with the demise of three institutions in March 2023. The obvious question arises: is the EMI sector is due its own crisis?[6]

The FCA has not been blind to the growth of the industry, and now appears to be shifting focus from processing licence applications to compliance and enforcement. The FCA has raised industry specific concerns via a portfolio-wide “Dear CEO” letter on four separate occasions in the last four years,[7] following the publication of its approach to supervising e-money in 2017 which has been revised several times since. [8]

In July 2019, following a review of safeguarding arrangements at a small sample of firms,[9] the FCA identified “significant shortcomings” in firms’ safeguarding arrangements. This caused the FCA to write to the company CEOs, requiring firms to make a formal attestation that they had “carried out a review of its safeguarding procedures taking into account the guidance”.[10]

A year later in July 2020, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the FCA again called on payment and e-money company CEOs to “act to prevent harm to your customers”, expressing that it was “concerned that consumers may not understand the lack of protections they have”.[11] The FCA reminded firms of their obligations under the regulations and drew firms’ attention to “six key areas where non-compliance with these obligations harms consumers”.

In May 2021, the FCA wrote to e-money company CEOs, asking them to act to “ensure your customers understand how their money is protected”.[12] In particular, the FCA stated that they were “still concerned that many e-money firms are not adequately disclosing the differences in protections between their services and traditional banking”.

As recently as March 2023, the FCA wrote to CEOs setting out their priorities for payment firms, asking firms to take action focused on three outcomes: “(i) ensure that your customers’ money is safe; (ii) ensure that your firm does not compromise financial system integrity; and (iii) meet your customers’ needs, including through high quality products and services, competition and innovation, and robust implementation of the FCA Consumer Duty”.[13]

Given the additional regulatory costs placed on EMIs and PIs by the FCA, combined with a challenging economic climate and the general falling confidence in the banking sector, the prospect of EMIs raising additional capital is diminished. This introduces the possibility that one or more EMIs may fail.

There are already reports of ‘zombie’ firms that appear neither dead nor alive, with customers stuck in limbo. In this situation, an EMI has refused or been very slow to return customer funds immediately when requested, yet it is not in administration and neither the firm nor the FCA has offered any substantive reason for the delay. In some cases, the suggestion is that the firm has had to make improvements to its anti-money laundering controls, before releasing funds.

Conclusion

The line between bank and non-bank provisions of financial services is increasingly blurred due to the significant growth in the number and use of EMIs and PIs. These firms are taking advantage of a lighter regulatory regime which has not been in place for long and these firms have largely operated under benign conditions. The FCA is now increasing its scrutiny of the sector, taking up enforcement action (e.g., revoking licences). A large proportion of the firms operating today are likely to be unprofitable and reliant on venture capital, which is drying up. An uptick in business failures is inevitable.

We are likely to see disputes arise in three main areas:

[1] TechCrunch, dated 17 March 2016. [https://techcrunch.com/2016/03/17/open-for-spending]

[2] The Guardian, UK ministers ask to meet Revolut amid reports it may be refused licence, dated 19 May 2023. [https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/may/19/uk-ministers-revolut-licence-fintech-firm]

[3] Financial Conduct Authority dated 13 March 2023. [https://www.fca.org.uk/consumers/using-payment-service-providers]

[4] What Do They Know, dated 24 March 2023. [https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/size_and_development_of_the_uk_e]

[5] What Do They Know, E-money transaction volumes and values including fraud figures, dated 24 May 2023. [https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/e_money_transaction_volumes_and]

[6] Signature Bank, Silicon Valley Bank and Silvergate Bank.

[7] Financial Conduct Authority, Dear CEO letter, dated 4 July 2019. [https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/correspondence/dear-ceo-letter-non-bank-payment-service-providers-requirements-for-safeguarding-of-customer-funds.pdf]

[8] Financial Conduct Authority, Payment Services and Electronic Money – Our Approach, dated November 2021. [https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/finalised-guidance/fca-approach-payment-services-electronic-money-2017.pdf]

[9] Financial Conduct Authority, Safeguarding arrangements of non-bank payment service providers, dated 4 July 2019. [https://www.fca.org.uk/publications/multi-firm-reviews/safeguarding-arrangements-non-bank-payment-service-providers]

[10] Financial Conduct Authority, Safeguarding Attestation – Electronic Money Institutions. [https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/forms/safeguarding-attestation-authorised-payment-institutions.pdf]

[11] Financial Conduct Authority, Portfolio strategy letter for payment services firms and e-money issuers, dated 9 July 2020. [https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/correspondence/payment-services-firms-e-money-issuers-portfolio-letter.pdf]

[12] Financial Conduct Authority, Dear CEO Letter, dated 18 May 2021. [https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/correspondence/dear-ceo-letter-e-money-firms.pdf]

[13] Financial Conduct Authority, Portfolio Letter, dated 16 March 2023. [https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/correspondence/priorities-payments-firms-portfolio-letter-2023.pdf]

[14] Judgement in the matter of Ipagoo LLP, dated 9 March 2022. [https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/In-the-Matter-of-Ipagoo-In-Administration.pdf]