Introduction

“There are no straight lines or sharp corners in nature” stated the architect Antonio Gaudi, and this can be applied to oil and gas reservoirs, which bear no resemblance to the neatly drawn blocks overlaid upon a map to allocate exploration and production licencing rights. Reservoirs are complex in shape due to geology and other parameters such as fluid composition and often cross the artificially defined licence boundaries of blocks as well as, sometimes, international boundaries.

Unitisation and Redetermination (“U&R”), refers to various processes, analyses, studies and agreements that are implemented to enable an oil or gas field that straddles one or more blocks to be considered as one “Unit” and, hence, developed in the most efficient manner. Specifically, Unitisation refers to the process where the various licensees of the blocks which the field straddles will trade their individual block interests for an interest in the overall Unit. Meanwhile Redetermination refers to the process that occurs later in the field life, where an opportunity is provided to modify the original Unit interests allocated to each party to revised interests based on new information acquired during the development and production of the field.

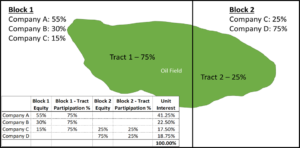

A simple example of Unitisation is shown in the figure below. An oil accumulation (in green) is found to cross the boundary of two adjacent blocks (Block 1 and Block 2). Communication, often determined by pressure readings from wells, is established between the reservoir in Block 1 and that in Block 2 so it can be considered one oil field.

The reservoir straddling the license boundaries is referred to as the Unit. Analysis shows that the part of the Unit sitting in Block 1 contains 75% of the oil (Tract 1) with the remaining 25% of the oil in the part of the Unit sitting in Block 2 (Tract 2). The Tract Participation (“TP”), for the Block 1 consortium is therefore 75% and the TP for the Block 2 consortium is 25%. The Unit Interest for each company within the consortia is their block license ownership percentage multiplied by the relevant TP.

Typically, the parties will enter into a Pre-Unitisation Agreement and later a Unitisation and Unit Operating Agreement (“UUOA”). The UUOA will normally include a provision stating it has supremacy over any Joint Operating Agreements entered into for each license within the area covered by the UUOA.

Processes for U&R

The Unitisation process is relatively simple, but its implementation is complex. Firstly, and vitally, how is the oil contained within the Unit measured and allocated between the Tracts? When dealing with the subsurface, be it for Reserves estimation or for Unitisation and Redetermination, it is not possible to actually measure oil or gas volumes; they can merely be estimated. Unlike Reserves estimation where a range of volumes (low, best and high or 1P, 2P and 3P) are reported, Unitisation requires a single estimate for hydrocarbon volume to define TP.

Hydrocarbons can be estimated as a measure of hydrocarbons in place (Stock Tank Oil Initially in Place (“STOIIP”) and Gas initially in Place (“GIIP”)) or a measure that takes into account the recovery of oil or gas, such as Estimated Ultimate Recovery (“EUR”) which is a portion of STOIIP (or GIIP) or an estimate of Reserves. STOIIP or GIIP provides the simpler basis as there are less variables. For example, estimating Reserves requires that they are economically viable to recover and hence a prediction of future oil and gas prices is required.

Once the basis for estimation is agreed, the procedures for obtaining that estimate require clarification. There are significant commercial implications arising from the allocation of TP, possibly hundreds of millions of dollars for a 1% change in TP in larger fields. If the field has been developed and produced before the TPs are determined (or redetermined), then there may be millions of dollars to be repaid by one Tract to the other for the adjusted share of both costs and revenues. This can then lead to further disagreement as to how these imbalances are rectified and repaid.

The nature of hydrocarbon estimation is that there are numerous potential approaches, interpretations, analytical methodologies and calculation procedures that can be used. Guidelines can and should be provided in Pre-Unitisation Agreements but there is still scope for differing decisions and approaches regarding issues such as depth conversion and petrophysical interpretation.

In the example shown above, a further complexity is Company C being a minor shareholder in both blocks and therefore, potentially, having conflicting interests in setting the TP. One might think having one company in both blocks may simplify the process, but this is often not the case. The company is unlikely to be permitted to share data relating to each block with partners in the other block, or even internally (depending on the data sharing provisions agreed), and it is not unusual to see conflicted companies necessarily supporting opposing stances for the different blocks in U&R.

Even on a matter as fundamental as establishing if an accumulation can be considered as one Unit, there can be disagreement. Our team have seen cases where parties on a smaller neighbouring Tract have pushed for Unitisation with a neighbouring block without proving communication to the satisfaction of all parties, leading to early disputes on whether Unitisation is even required.

Promoting Agreement in U&R

U&R can, due to its high economic stakes, its technical complexity and the fundamental uncertainty in hydrocarbon estimations, develop into the prefect recipe for fostering grievances between parties who will, post Unitisation, need to continue to work together.

The use of experts can help the process to run smoothly. Normally experts only get involved after the UUOA has been reached and these agreements typically define how the expert must operate. The huge pressure on companies to rapidly agree UUOAs can lead to the agreements including generic provisions, or terms that are not fit-for-purpose. For example, it is very difficult in the early days of reservoir appraisal to accurately model its full production life and some UUOAs define estimation procedures that may, in time, prove an ill fit for the reservoir. In addition, it is notoriously difficult to predict the evolution of technology. For example, many Unitisation agreements for large North Sea fields were written in the 1970s and did not anticipate the onset of horizontal drilling. The agreements therefore exclude some data acquired from such wells from the U&R process, even when it reveals a distinctly different picture.

No matter how inappropriate some provisions may be, they will typically benefit one party who will resist any change to those terms. Any change to a UUOA usually requires unanimous assent and therefore hastily agreed terms in Pre-Unitisation Agreements or UUOAs can be a source of future problems. Consequently, one proactive step to facilitate future agreement is the earlier engagement of experts, specifically to include expert input into the definition of the UUOAs. This should help improve the workability of UUOAs, reducing impractical terms before they are set in stone.

An alternate methodology aimed at avoiding lengthy Unitisation processes is to initially implement a very simple UUOA with minimal attempt to accurately estimate TPs. This enables field development to begin promptly and, hopefully, for cash flow to be established earlier than if a protracted Unitisation process was entered into. A Redetermination process is scheduled at a defined time in the development when there will be considerably more data available. This enables a more robust reservoir model to be developed and history-matched against real life performance of the field over time. This model then forms the basis of TP estimation. The newly defined TP percentages are retrospectively applied to all previous production thus, in theory, ensuring that there is no downside to the original simplified agreement.

There is of course no guarantee that the Redetermination process will easily be agreed upon but greater data availability and a more robust understanding of the field is a good basis for discussions. However, Redeterminations can cost millions of dollars and in smaller, economically marginal fields, the Unitisation agreement may not allow future Redeterminations as their high cost may tip the balance of an already marginal field.

Other steps that can be taken to facilitate the U&R process include clarifying data exchange processes early (each Tract will initially have its own dataset). This may include negotiating a confidentiality agreement and the scope of data that will be exchanged to avoid future issues. Data exchange can, at best, be a lengthy process in non-contentious U&R and can be a potential battleground in contentious processes.

The role of the government or a national oil company should also be defined, clarified and, as far as possible, adhered to. U&R experts can be engaged upfront to assist governments, especially in frontier areas, to define the overall petroleum legislative framework including U&R provisions. Governments will likely seek to maximise their fiscal take from any project, and possibly promote the interests of indigenous firms, but should not be able to slow down U&R processes where equity partners have agreed a way forward.

Conclusions

Overall, no single tactic can be deployed to ensure the smooth running of a U&R process and with the stakes high and the methodologies open to debate there remains much potential for dispute. It is vital that early agreements (Pre-Unitisation Agreements and UUOAs) are fit-for-purpose and their provisions are not likely to cause issues in the future. Engagement of suitably experienced experts in the drafting of these agreements should help to clearly set out fit-for-purpose methodologies that balance the need for sufficient detail and clarity on methodology whilst avoiding overly prescriptive terms.

Where U&R disputes do arise, the engagement of experts can help parties reach agreement. The appointed expert will need a combination of both technical and commercial expertise in order to address the broad range of issues involved in U&R. Experience of working on previous U&R is essential and such experience will help ensure that decisions are commercially justified as well as being legally based and technically sound.

Finally, it should always be remembered that whilst it may seem tempting to fight every point to get the best possible UUOA, no oil or gas field ever made money until it was brought into production.